RISORGIMENTO

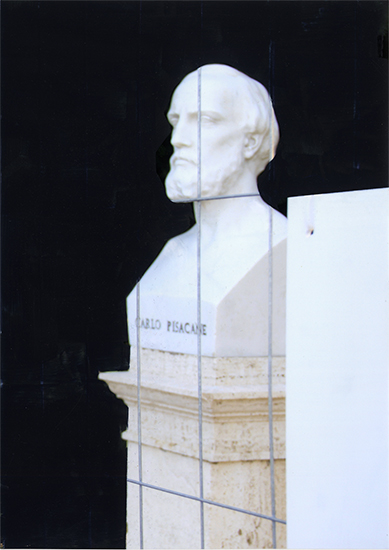

The unification of Italy during the 19th century, the Risorgimento, proved to be a long and convoluted process beginning early in the century and culminating in 1871 with the establishment of Rome as the capital of what was to become a modern nation state. The last phases of the unification, during the period 1848-1870 were orchestrated by the charismatic Guiseppe Garibaldi.

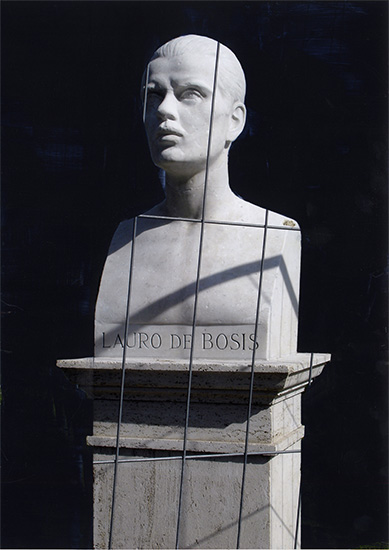

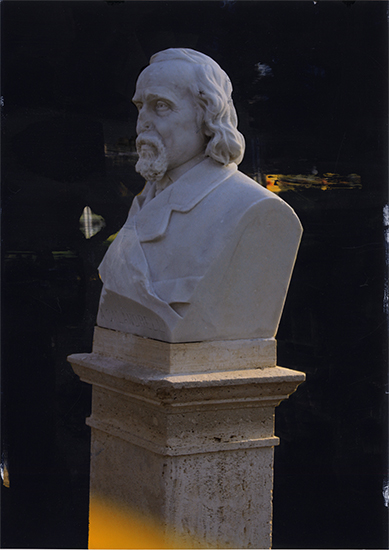

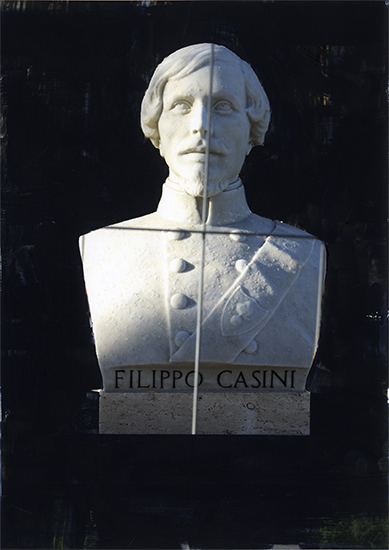

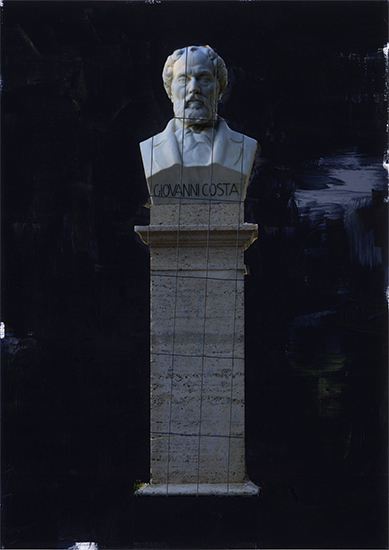

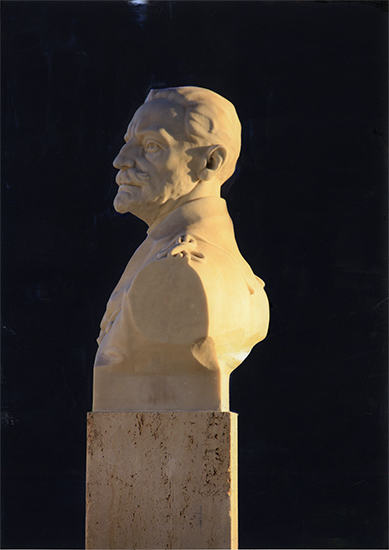

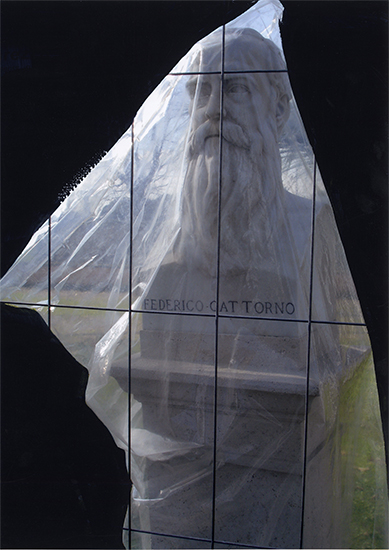

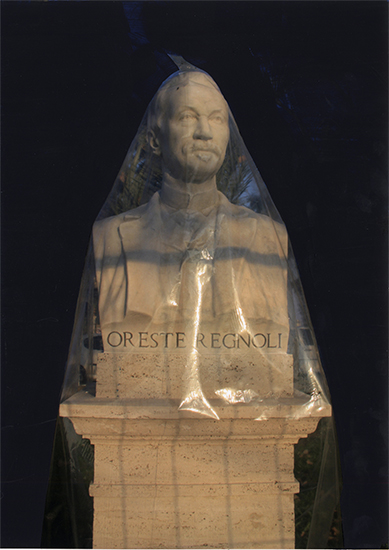

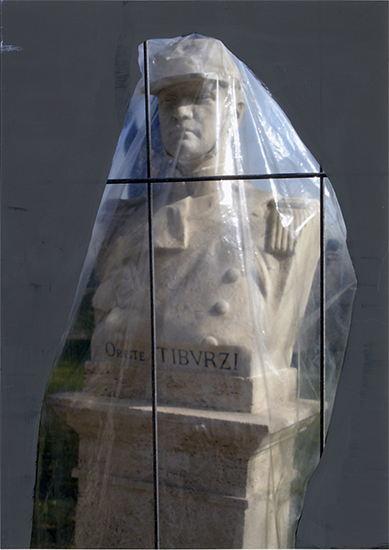

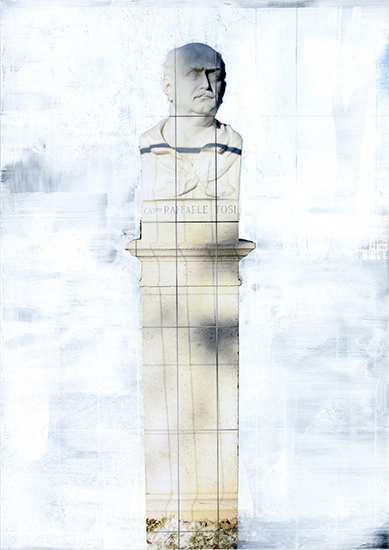

Garibaldi and his colleagues are memorialized in a park on the Janiculum, a hill rising above Trastevere overlooking Rome. At the center of the park stands a monumental 25 meter high equestrian bronze sculpture of Garibaldi. Lining the three streets leading into the park and converging on the monument to Garibaldi are 83 portrait busts of his supporters, carved in stone (with the exception of one in bronze) and mounted on pedestals. It is this collection of portrait busts that forms the subject of my project.

My first encounters with the portrait busts in the mid 1990’s were characterized by a curiosity about their monumental form and function. I was familiar with the format from portrait busts in the Borghese gardens of poets, philosophers and politicians primarily from the ancient period, but this grouping had a much more focused historical relevance.

In addition they generated a very real sense of nostalgia, due in large part to their deep patina, verging on states of neglect, amplified by being placed in a particularly romantic setting, among equally monumental London Plane trees imposing a shifting of dark and illuminated spaces throughout the park, on the crest of a hill with all of Rome spread out below. Their function in recalling the epic struggles to form a unified state had the effect of reinforcing an historical distance between that struggle and the current condition of the state. Perhaps this is always the case with the aging of monuments that mark significant historical events. They become contemporary to the subjects they represent. Over longer periods of time, the significant differences in modes of representation and style apparent at a given moment soften. The characteristic use of neo-classical and other pre-modernist motifs reinforces their linkage to the past.

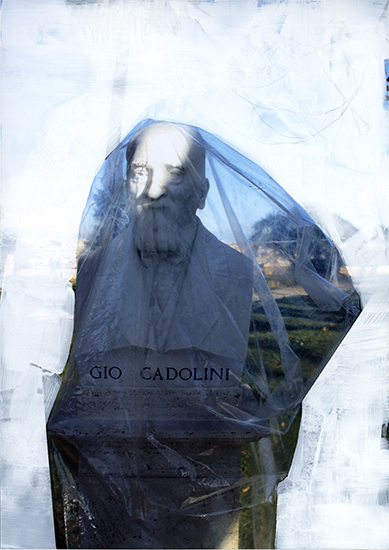

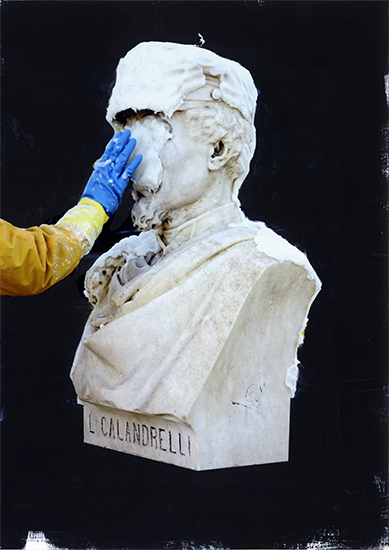

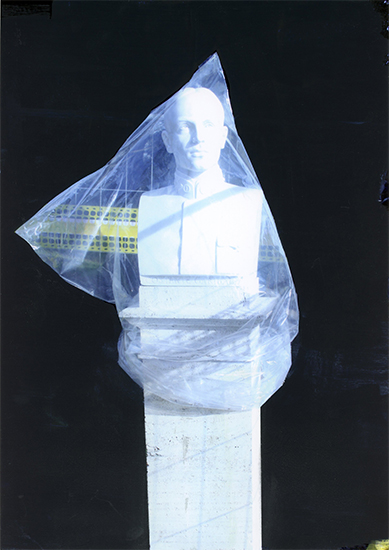

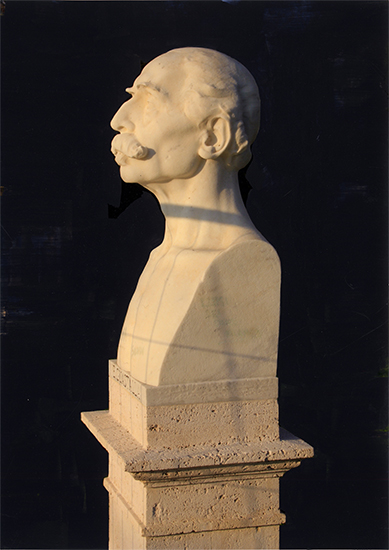

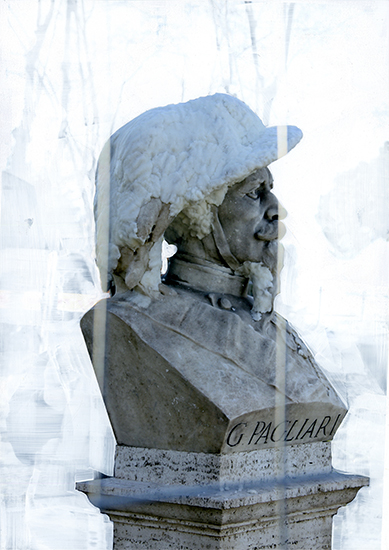

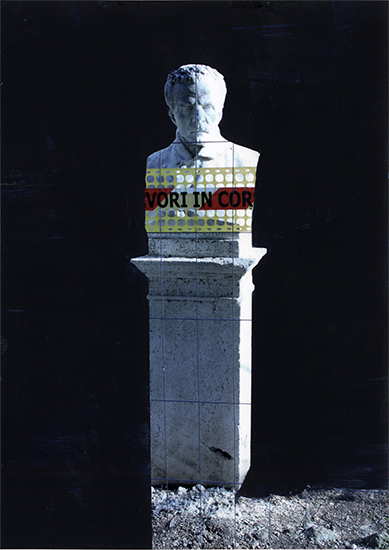

The restoration of monuments signals of course an institutional commitment to acknowledging the significance of historical events and figures, a concern for preservation. I think that there is also an affect of restoration that provides a means of linking those historical events with the present (the freshly cleaned, and therefore “contemporary” state of things). The monuments, at least for a time, seem as much of the present as of the past. The result of the restoration of the Gianicolo monuments brought them strikingly into the moment for the celebration of the 150th anniversary. A year, two and now three years later, the brightness is softening, the patina developing and they begin to slip, very subtly again into the past.

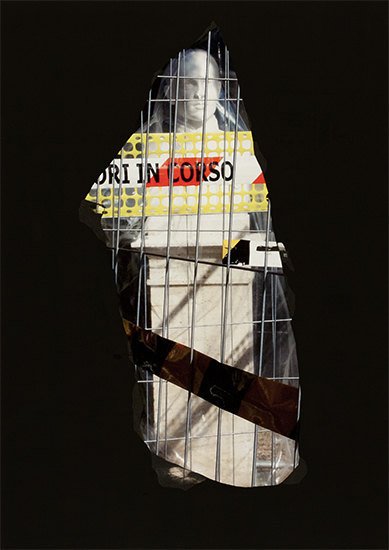

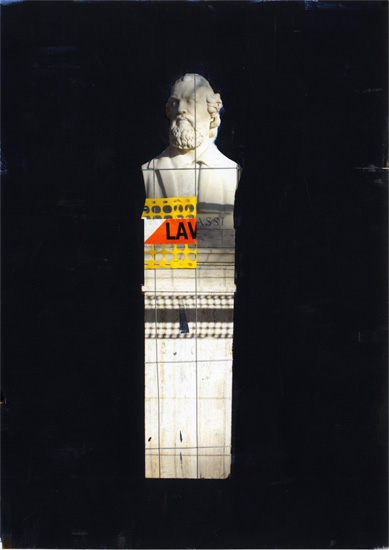

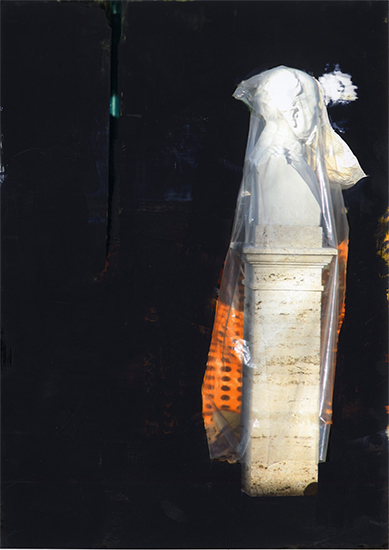

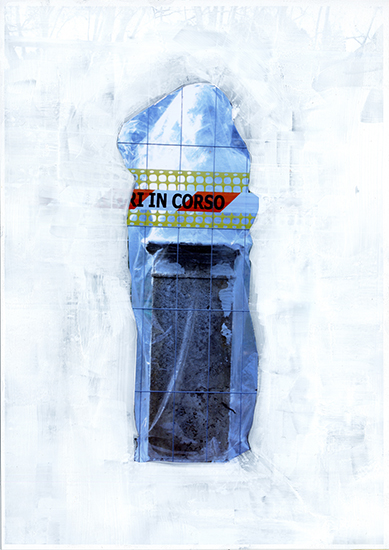

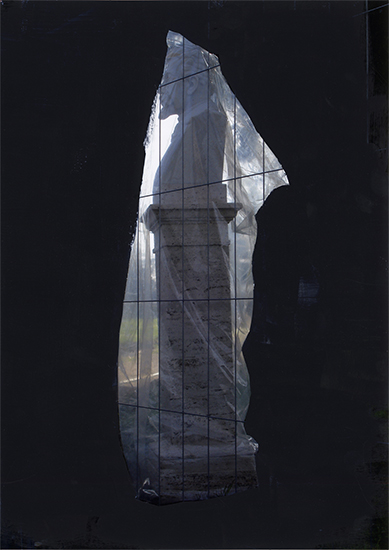

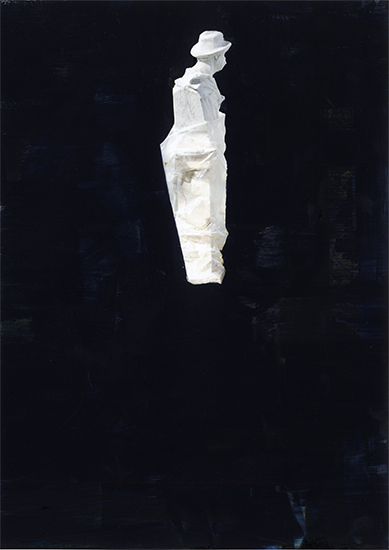

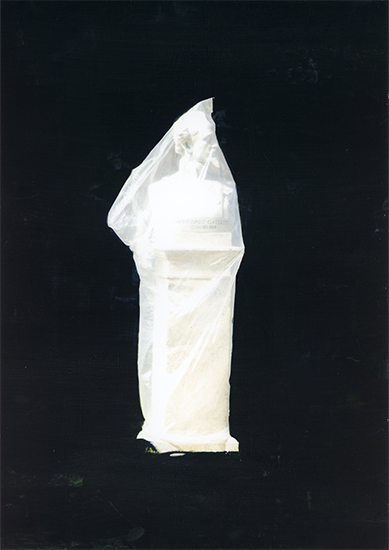

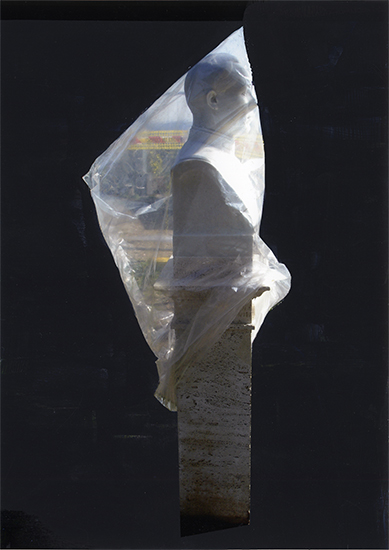

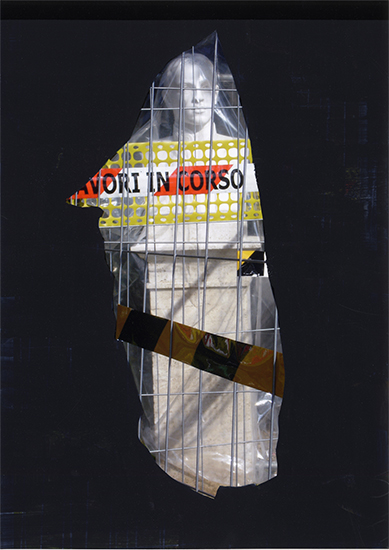

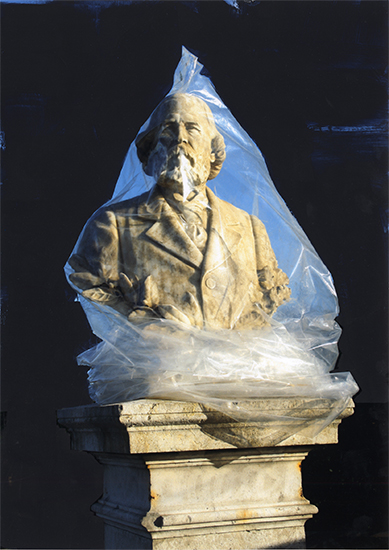

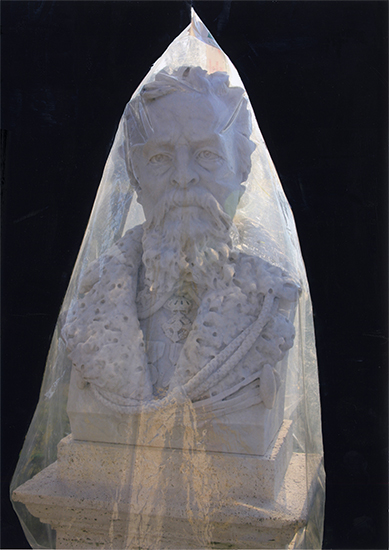

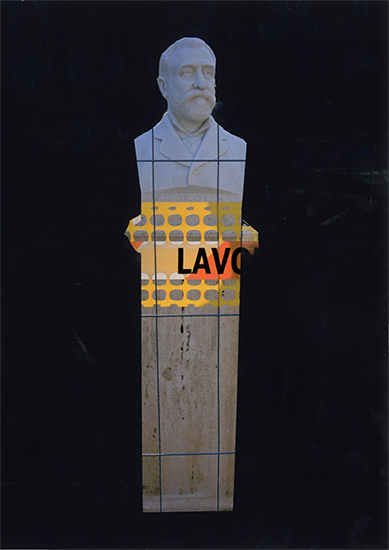

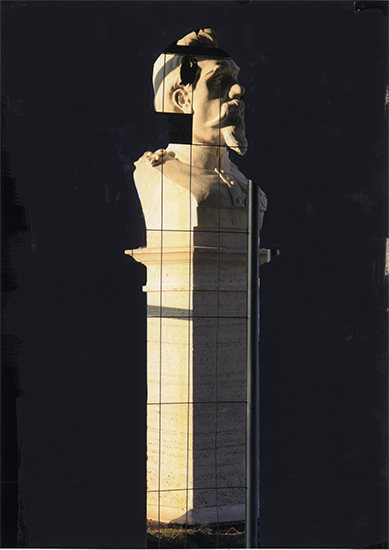

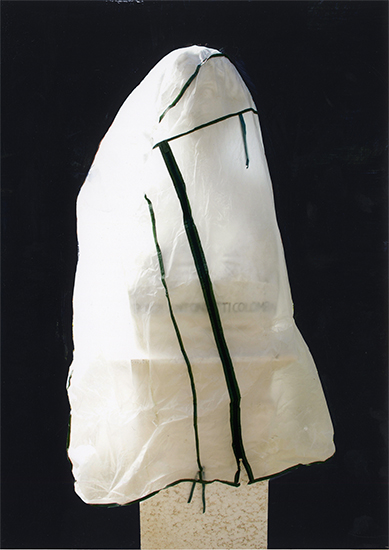

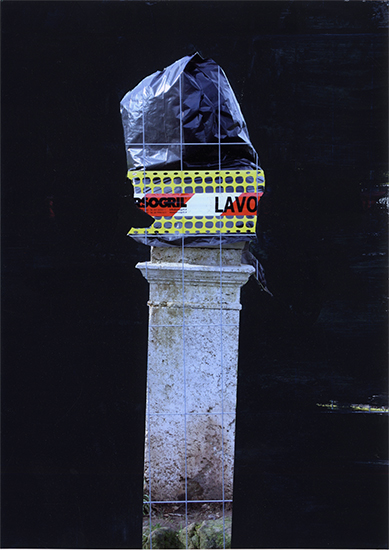

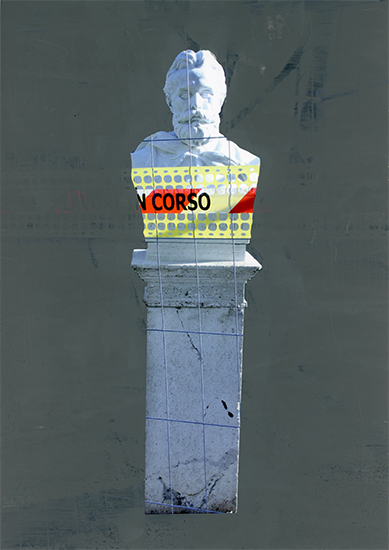

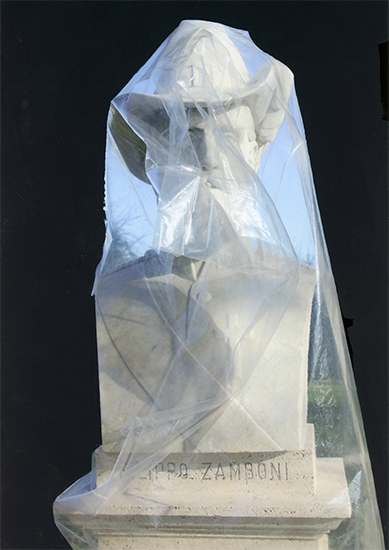

In January of 2011 I was surprised to witness the preparatory cleaning and restoring. Scores of conservators worked on the sculptures behind fencing and caution tape. The sculptures themselves were in various states of restoration with just a few seemingly completed. Sitting behind the fencing and caution tape, wrapped in plastic, being treated by the conservators, the busts took on a much more animated character than I had observed in the past. Perhaps the plastic, cleaning compresses and impositions forced them to resist, in a way, to push back. They seemed to challenge the passivity that characterizes such monuments.